By Joke Kujenya

THE NUMBERS don’t lie—women’s health is in crisis, and the world isn’t paying enough attention.

From the United States to Nigeria and beyond, women are living shorter lives, facing higher risks during childbirth, and dealing with a healthcare system that often treats them as an afterthought.

Experts say it’s time for urgent action.

Twenty-nine-year-old Aisha Bello, a mother of two expecting her third child in northern Nigeria, was a victim of maternal neglect.

Living in a rural village outside Kano, she had limited access to healthcare. While she had given birth before, this time was different.

She suffered from prolonged labour—a joyous occasion turned desperate struggle.

With the nearest clinic over 30 kilometers away and no ambulance service, her husband transported her by motorcycle.

By the time they reached the hospital, Aisha was unconscious.

The clinic lacked proper equipment and referred her to a larger hospital in Kano city.

The delay proved fatal.

Aisha suffered an obstetric hemorrhage—a leading cause of maternal mortality in Nigeria.

Without enough blood for transfusion, she passed away, leaving behind her newborn and two young children.

Nigeria has one of the world’s highest maternal mortality rates, with 1 in 22 women facing the risk of dying during childbirth. Experts stress that preventable deaths like Aisha’s could be avoided with better healthcare funding, emergency services, and trained medical personnel.

U.S. Women’s Lifespan Cut Short

WOMEN in the United States should be living longer, healthier lives, yet life expectancy has stalled and, in some cases, declined.

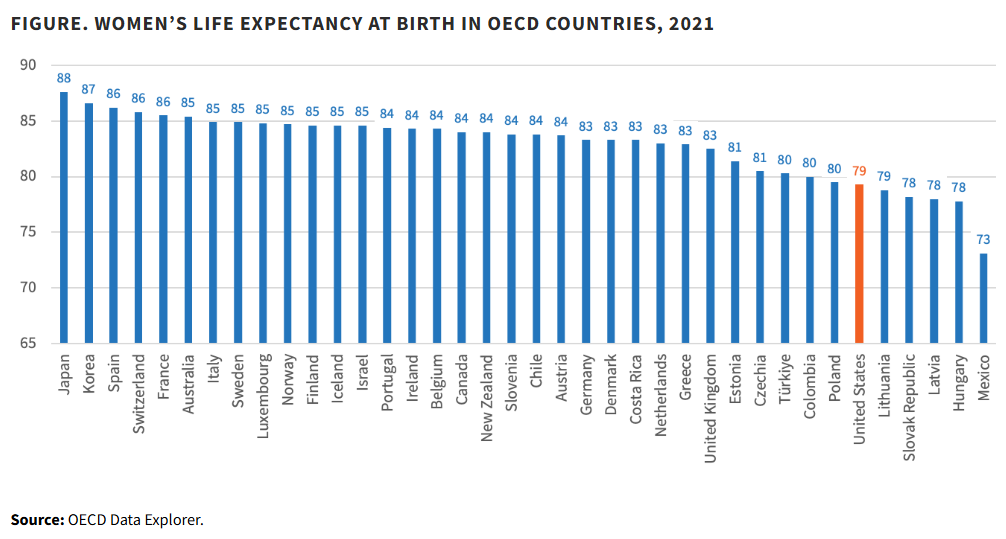

According to the Population Reference Bureau (PRB), American women’s life expectancy stands at 79.3 years, far behind Japan’s 87.6 years.

Obesity, smoking, substance abuse, and mental health struggles contribute to the issue. However, deeper systemic problems—racial disparities in healthcare, underfunded women’s health research, and economic inequality—play a larger role.

In Nigeria, life expectancy for women is just 56 years due to high maternal mortality, infectious diseases, and poor healthcare access. South Sudan’s ongoing conflict leaves women particularly vulnerable, lacking even basic medical services.

Maria Lopez, a 44-year-old teacher in Texas, was another victim of a broken system. A mother of three, she prioritized her family over her health.

When she experienced persistent fatigue and irregular bleeding, she delayed medical attention due to lack of health insurance.

By the time she was diagnosed with stage 3 cervical cancer, it was aggressive but still treatable—if caught earlier.

However, she was placed on a waitlist for chemotherapy due to an overcrowded public health system.

Private care was unaffordable. By the time she was admitted for intensive care, the cancer had spread. She passed away within months.

Cervical cancer is highly treatable when detected early, yet uninsured women and those in low-income communities face delayed diagnoses and inadequate treatment.

Across Africa, maternal mortality remains a crisis.

Nigeria alone accounts for nearly 20% of global maternal deaths.

Women die from preventable complications simply because they lack access to quality prenatal and postnatal care.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Nigeria recorded 1,047 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2020, one of the highest rates in the world.

In Sierra Leone, one of the most dangerous places to give birth, efforts to decriminalize abortion could reduce unsafe procedures contributing to high maternal death rates, yet resistance remains strong.

In Uganda, while mobile clinics and community health workers help, a shortage of trained professionals means many women still give birth without skilled assistance.

Even when women outlive men, women spend more years battling disability.

Chronic illnesses, mobility issues, and conditions like osteoporosis and autoimmune diseases disproportionately affect them.

In the U.S., older women’s “active life expectancy” is increasing at a much slower rate than men’s.

In African nations like Ethiopia and Ghana, rising rates of diabetes and hypertension go untreated due to limited elder care resources.

Rising Toll of Mental Health Crises

Young women face growing threats.

Suicide and homicide rates have surged, particularly among women of colour. In the U.S., young Black women are 60% more likely to be murdered now than two decades ago.

Indigenous communities see suicide rates among young women three times higher than their white peers.

In conflict zones like the Democratic Republic of Congo, gender-based violence remains rampant. Displaced women face daily threats, often forced into dangerous situations just to survive.

In South Africa, a woman is killed every four hours, according to government statistics. Activists call for stronger legal protections and increased funding for shelters and support services.

Calls for Intensified Research

For decades, women’s health has been underfunded.

In the U.S. the National Institutes of Health (NIH) dedicates less than 9% of its budget to women’s health research, slowing progress in areas like reproductive health and chronic disease prevention.

African nations also face research funding gaps.

While some progress has been made in HIV/AIDS research—where African women are disproportionately affected—maternal health, cancer, and mental health remain critically underfunded.

The African Union urges governments to allocate at least 5% of GDP to healthcare, but most fall short.

A proposed Women’s Health Research Institute in the U.S. could be a game-changer, prioritizing women’s health across all life stages. Experts say such initiatives are critical for ensuring equitable healthcare.

Women’s Health Concerns As A Global Priority

Women’s health is fundamental to the well-being of families, homes, societies, economies, and future generations.

Governments are urged to make funding research a must, improve healthcare access, and address systemic inequalities.

The reality is clear: when women’s health suffers, entire communities pay the price.

My question is—how much longer will the world wait before taking action?