By Jemimah Wellington, JKNewsMedia Reporter

IN A scathing critique of international financial institutions, Akinbode Oluwafemi, Executive Director of Corporate Accountability and Public Participation Africa (CAPPA), presented a damning report that unveils how World Bank-backed water privatisation reforms have failed to address Nigeria’s growing water crisis.

Despite billions of dollars in loans, local communities remain deprived of reliable water access, while the debt burden continues to mount.

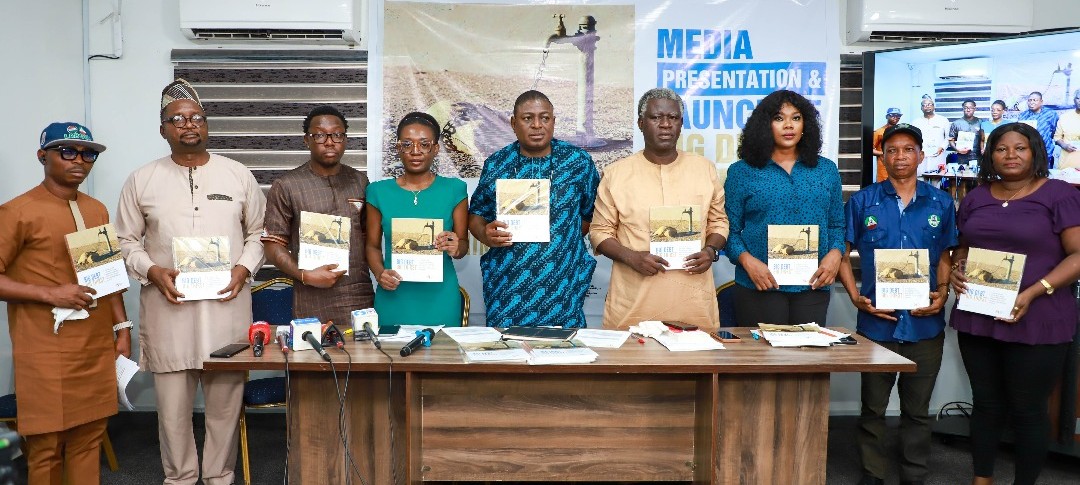

The report, titled Big Debt, Big Thirst: A Case Study of World Bank Supported Projects in Ekiti, Rivers, and Bauchi States, delves into the enduring consequences of privatisation and corporatisation schemes that have been hailed as solutions to the country’s water woes.

However, CAPPA’s findings challenge this narrative, pointing to an alarming pattern of inefficiency, lack of accountability, and worsening conditions for local residents.

Oluwafemi’s address to the media at the report’s presentation reflected the continuing failure of privatisation-driven reforms, spearheaded by the World Bank’s Third National Urban Water Sector Reform Project (NUWRSP3).

The project, backed by a $250 million loan from the International Development Association, promised modernised infrastructure and greater efficiency.

However, five years after completion, many of the promises remain unfulfilled, with communities in Ekiti, Rivers, and Bauchi states facing steep water tariffs, inadequate services, and unaddressed systemic issues.

In Ekiti State, residents of areas like Iworoko and Olorunsogo, who invested heavily in prepaid water meters and connections, are still without consistent access to potable water.

“People often reminisce about the 1990s when public water systems were more reliable,” says a local resident, reflecting the widespread disappointment in the shift towards privatised water management.

Similarly, in Bauchi, chronic water shortages persist despite infrastructural upgrades intended to address the crisis. CAPPA’s research links this failure to persistent electricity shortages, emphasising the interconnected nature of public services and the limitations of market-driven solutions.

Rivers State, which had received both World Bank and African Development Bank funding for water projects, experienced significant delays due to poor coordination and procurement issues, with the World Bank eventually withdrawing its support.

The fallout left millions of residents in Port Harcourt and surrounding areas without improved water access, compounding the widespread frustration.

The financial burden of these failed reforms is heavy. The loans, denominated in foreign currency, have created long-term debts that Nigerians will be paying off for decades.

Meanwhile, the core problems—lack of reliable power supply and inadequate infrastructure—remain largely unaddressed.

Oluwafemi’s address also critiqued the ideological foundations of these reforms, highlighting how neoliberal policies pushed by institutions like the World Bank have undermined public control over essential resources.

By prioritising market-driven approaches over the public good, these reforms have exacerbated socio-economic disparities and fostered long-term dependencies on external debt.

The report calls for a paradigm shift in how water governance is approached in Nigeria. It advocates for water to be recognised as a fundamental human right, not a commodity to be traded.

The authors argue for increased public investment in water infrastructure, better governance practices, and stronger community involvement in decision-making processes to ensure sustainable and equitable access to water.

Oluwafemi notes that as the debate around privatisation versus public management continues, CAPPA’s report affirms the urgent need for a reevaluation of the strategies that have been imposed on Nigeria’s water sector.

He adds that the essence of the findings challenges the prevailing narrative that privatisation is the solution to the country’s water crisis and call for a renewed focus on public investment and democratic control over this vital resource.